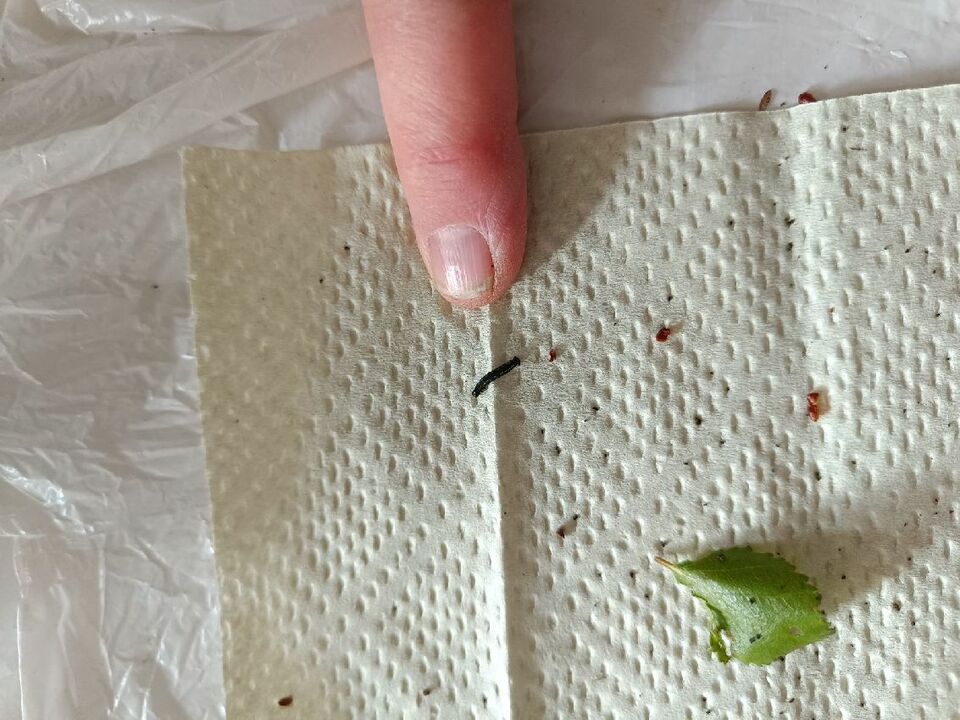

A mountain birch leaf and a moth larva on a laboratory desk at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station.

Travelling north

It’s an unusually hot Friday evening near the midsummer of 2025. I’m seated on a packed train leaving Pasila station in the Helsinki suburbs. The crowd signals the start of the holiday season. Students returning home, some foreign workers, many hikers, cyclists, and dogs — travelling overnight, we are all heading north. The train is bound for Kolari. From there, I’ll continue for more than three hours by car to the Finnish-Norwegian border.

I’m on my way to the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station, arriving as part of the “Rewilding Cultures” residency program. I’m thrilled to have this opportunity. The residency allows me to spend two weeks at the station and explore the Kilpisjärvi area, which is ecologically unique: post-glacial landscapes with alpine tundra, mountain birch forests, and special sedimentary rocks that support rare biodiversity. The biological station, situated on the edge of Lake Kilpisjärvi, has allowed for rare long-term scientific observations, advancing understanding of natural variation, population dynamics, and the impact of climate change. And yet the region is not a pristine wilderness. It has been inhabited since the last Ice Age and has long been home to the Sámi people, who for millennia have shaped the landscape along seasonal reindeer movements. Kilpisjärvi is significant both as a site where environmental knowledge and imaginaries have taken shape, and as a place that challenges some enduring concepts of nature — especially the romanticized divide between the wild and the cultural — that remain deeply embedded in cultural and scientific frameworks.

Still, I also sense some apprehension. Travelling north, as I am doing now, is not a neutral gesture. Since the Enlightenment, scientific journeys to the northern European territories — then broadly referred to as “Lapland” and framed as terra nullius — have critically shaped European ideas of nature and wilderness. These expeditions were foundational to forming environmental science, but they were also motivated by and entangled with colonial expansion and extractive ambitions. I think of the binomial system of naming species, developed by Carl Linnaeus after his 1732 scientific journey to northern territories (later published as Flora Lapponica). Combining botanical enthusiasm with broader explorations and the prospecting of natural resources, the scientist developed the universal Latin two-name system still used in biological classification today. The system has been exceptionally useful for advancing collective environmental knowledge. But also, it gained lasting popularity in part because it offered a practical tool for cataloguing the growing influx of specimens from colonial expeditions worldwide. I’m reminded of these long-naturalised histories by a book I am travelling with, Botany of Empire, by botanist and feminist scholar Banu Subramaniam.¹ The ongoing (socio)ecological crises create a sense of urgency and pressure to look past the “past” and focus solely on science’s role in securing a livable future. Yet, as Subramaniam writes, these historical entanglements are not behind us; they are intertwined in the conceptual frameworks and environmental imaginaries we continue to use. They carry with them blind spots and reproduce exclusionary divisions: Whose knowledge is valued? Who gets to be considered an expert? Who or what is deemed expendable in the name of progress? The question is no longer only what we should know, but how we come to know and at what cost?

These questions don’t negate my joy in travel. But rather than retracing the footsteps of past explorers affirmatively, I feel a need to pause, and find time and space to think about my inherited academic training, thinking with practitioners whose environmental work embeds scientific tools within their social and historical contexts. Not to diminish the legitimacy of environmental science, but, in Subramaniam’s words, to make space for richer epistemologies that are not outside of science but cultivated from within. Seen through this lens, the call for “rewilding cultures” becomes more than a theme: it invites reflection on the assumptions we inherit that shape our habits of knowing (and hence doing) ecology. Can the idea of rewilding cultures help us think differently about scientific cultures (such as expeditions, taxonomic classification, and the production of field-based authority) and the imaginaries they generate within artistic and political life?

Kilpisjärvi’s mountain birch landscape with Saana Fell on the horizon.

Rewilding

In my experience shaped by environmental training, rewilding is closely tied to the scientific framework of restoring ecosystems to a “natural” state (often imagined as pre-human or pre-industrial) by reintroducing keystone species and minimizing human control. But this relies on a paradox: wildness, which by definition resists mastery, measurement, and fixed categorization, becomes itself a normative framework — something predefined, pursued, and managed. Is it possible to rewild not just landscapes, but the systems we use to understand them? Or, as queer theorist Jack Halberstam asks, can theory (and practice) itself be rewilded?2

The idea of “returning” to the wild is compelling, but not without risk. In current political contexts, one can think of the wild undoing of science infrastructures: dismantling institutions, erasing data, promoting regressive ideas of human nature. But as Halberstam notes, this intensified yet regressive return of “wildness,” reproduces white settler-colonial imaginaries, which frame the wild as external to culture, dangerous and unruly, and therefore in need of control, management, and extraction. Against the wildness shaped by the colonial gaze, realizing the full possibilities of rewilding means unlearning the inherited binaries (nature/culture, civilized/primitive, rational/irrational) that structure the world through hierarchy, positioning one domain as superior and entitled to dominate the other. This more introspective rewilding is not without risks. Working outside safe, established frameworks can bring bewilderment, disorientation, and uncertainty. But the uncertainty, even in discomfort, is not a deficit to be overcome; rather it is the ground from which more relational, joyous, and reciprocal futures could emerge.

Artist Kati Kärki with a stem of twinflower (Linnaea borealis).

Situating a botanical gaze

In my case, my journey into the wild continued in an ostensibly mundane way: I wanted to spend time outdoors without too rigid expectations (since I have been increasingly uneasy about what these should be). Still, I needed some structure to sustain focus and attention, so I planned daily walks along the scientific trails and hiking paths mapped in the area. To better understand the place, I paid attention to the information provided and noticed what is highlighted and why. I also wanted to create an alternative observational framework, so I decided to observe and learn about the plants I encountered along the way.

On some level, my focus on local flora has been prompted by the historical significance of the Nordic and Sámi territories for developing botanical classification. However, I am not a trained botanist — and perhaps that’s the point. While plants have long been central to scientific rationality and imperial naming systems, they have also eluded total enclosure. Modern botany sees plants through systemic mapping, advanced molecular techniques and standardized classification systems, but plant practices have always existed beyond expert domains, being used, cultivated, cared for, and known through embodied knowledge. They can offer points of ecological connection also to those who do not fit into the productivist ethos of expert science, allowing for slower, more partial, and less linear forms of attention. I needed this. As someone travelling with a very active and often bewildered four-year-old, I could not sustain the kind of expert gaze — detached, uninterrupted, and singularly focused — even if I wanted to. While care ecology was not the primary axis of my exploration, I had to work in a way that allowed care and research to co-exist.

So, doing what I can, I tried to practice a connective attention: learning to understand plants not as isolated specimens but as living, tangible connections between environmental conditions (soil, geology, air), multispecies relations, and social histories. In this way, plants guided my focus beyond rigid speciesism and its alignment with extractivism, grounding attention in the specificity of place and making visible the material and historical conditions that sustain life.

Walking outdoors was sometimes work, sometimes tourism, and sometimes part of caregiver responsibility. I collected field notes, photos, observations, and informally talked with stationed scientists and staff. I tried to be attuned not only to the landscape and plants, but also to how these shifting positions and situations shape how I think about ecology and environment. Perhaps the best way to describe my approach is what geographer Matthew Gandy calls attentive observation, a practice of staying with the sensory and material specifics of place without reducing them to data points. It is a mode that resists reductive abstraction and allows space for uncertainty and spontaneous encounter, “stepping off the epistemic path” to encounter what would otherwise remain unseen.

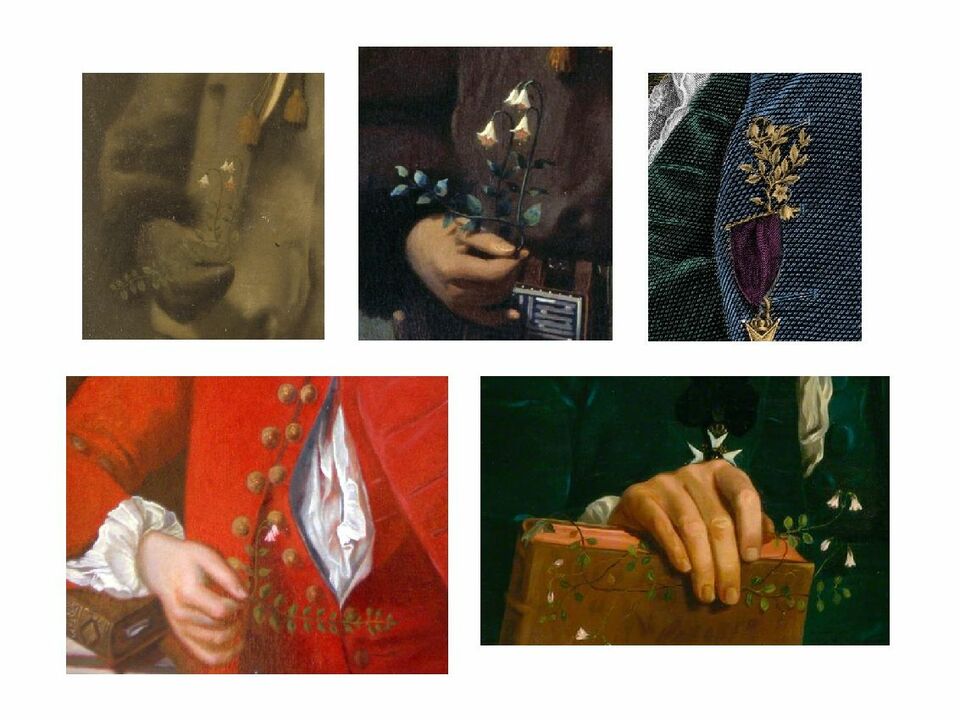

Linnaea borealisd epicted in many portraits of Carl Linnaeus. Image snippets sourced from the public domain.

Twinflower (17th June 2025, Salmivaara)

After several days of walking around, I began to think I wouldn’t find Linnaea borealis (twinflower). I was curious to see the species because of its symbolic significance: Carl Linnaeus named it after himself. He identified with the plant so strongly that it appears in many of his portraits, tucked into his coat or held in his hand, hidden in plain sight (this is where I first saw it). I knew it should grow nearby, but could not see it anywhere as it is a delicate plant, low to the ground, easily missed unless in bloom when its characteristic twin flowers show.

On a cloudy, slightly rainy afternoon, it was time to take the little one outdoors. Another station resident and artist Kati joined us, and we headed to the nearby hill. The child resisted the climb at first but eventually gave in, settling into a rhythm of wandering between rocks. I saw both of them moving slowly, their attention shifting from one thing to another, absorbed in whatever was around. The day before, we had hiked up Saana at a similar pace, distinctly lagging behind the flow of tourists who moved swiftly toward the distant peak. Today, neither of my companions seemed particularly interested in reaching the top. Their pace matched the kind of attention the botanical interest required and the steps a child was willing to take.

Kati, whose practice spans art and landscape ecology, knows a lot about the local flora and shares it generously. At one point, she paused and pointed to what looked like a dry twig near a patch of lichen-covered rock. “That’s last year’s Linnaea,” she said, guiding my gaze toward a brittle remnant pressed low against the moss, beside creeping stems with tiny, rounded leaves. They ran just above the ground, weaving between lichen, moss, and crowberry. That small gesture — Kati pointing, saying what it was — shifted something. After that, I started spotting twinflowers myself. They’d been there all along, but I hadn’t known how to see them. My view of the landscape became slightly more nuanced. Seeing the plant on my own felt meaningful and I better understood Linnaeus’s attachment. And, even more, I wished the species name reflected the plant’s delicate and relational growth, not the legacy of the one who named it.

Last year’s twigs of Linnaea borealis along the Salmivaara trail.

Angelica archangelica (18-26 June, Pikku-Malla trail and Saanajärvi)

The Kilpisjärvi station is situated between two distinct protected areas: the Malla Strict Nature Reserve and the Saana Nature Reserve. Walking the designated hiking trails, I was lucky to find many remarkable alpine tundra plants. Some, like Dryas octopetala (which grows just next to the main road) are paleohistorical relics, while others, such as Ranunculus glacialis, are notable for their adaptation to extremely cold climates. Diapensia lapponica, a small flowering plant that thrives in exposed and inhospitable environments, was locally abundant on the rocky slopes. Although Linnaeus named it after the places where he first encountered it, the species is actually circumpolar and even occurs in some parts of the Himalayas.

Amid these botanically distinctive species, one plant drew my attention for different reasons. Along the trail around Pikku-Malla, melting snow formed a temporary stream where young shoots of the water-loving herb Angelica archangelica sprouted. Later, I found a richer population in the stream behind Saana. I came across subtle reddish-green leaves, but in their second year, once fully grown, they will be hard to miss with their imposing, branched stems. In northern Europe, the wild subspecies of angelica is quite common. Its significance lies in its healing and edible qualities and in a long history of cultivation for food, medicine, and enjoyment as sweets or liquor. Dry stems can even be turned into musical toys. In Sámi traditions, it has been so important that the plant’s different growth stages and parts are named distinctly.⁴

For me, encountering this culturally important herb within a site of high conservation status had symbolic value. It reminded me that a plant’s significance is not limited to its rarity or threatened status; rather, plants are always already important because they sustain, nourish, and support. Angelica invites wondering how to expand ecological vocabularies beyond the binary of rare and common to appreciate the many roles plants play in ecosystems and human lives.

As I heard from a scientist working on a monitoring project in Malla, nature reserves are now critical refuges for many species displaced by pressures everywhere else, making their protection imperative. Yet unique ecological value does not make a reserve pristine or wilderness in the romantic or colonial sense. Here, ecological significance and value emerge from a dense fabric of naturecultural history and frictions between different environmental visions. Highlighting it at the expense of the romantic pristineness and wilderness is not a retreat from protection, but a step toward less limiting ecological imaginaries. Walking the meandering Malla’s trail, angelica shoots, along with solitary reindeer bypassing grazing restrictions, and the scars of WWII in the landscape reflect this.5

Angelica archangelica shoots growing next to Saanajärvi and on the Pikku-Malla trail.

Ecology of partial connections

The two weeks in the station and around it meant a rare moment of inner reflexivity and rest, something so many need but rarely get to experience. I could sense that I needed a break from the established rhythms of thinking. And, I could see for myself how the everyday acts of walking and observing can powerfully reshape one’s internal sensorium and shift our understanding of the outer world. Yet, unlike the familiar figure in environmental thought of the solitary thinker in nature, this was not my experience. My observations and the effects they had on me were also profoundly shaped by the infrastructures and connections that sustained us there. Being part of the Bioart Society residency opened a conceptual space and brought the comfort of knowing my personal perceptions were part of a broader context of questioning and reflection. Beyond that, the biological station was a place to retreat, recuperate, and pause. It also created proximity to the ongoing currents of scientific work. Days spent there put me alongside other resident artists, the station employees, and visiting scientists studying everything from greenhouse gas fluxes to ant molecular biology, plant protective tissues, and long-term species monitoring.

The scientists worked with high intensity, driven both by curiosity and the demands of academic productivity. Many adjusted their work to the sun that never set: one woke after midnight to start fieldwork at dawn, another ran tightly scheduled experiments that stretched past midnight, and another hurried to finish manuscripts before their grant ended. Yet, despite these pressures, many interrupted their work to share: a lichen expert helped identify specimens, a PhD student explained advanced plant morphology, a postdoctoral researcher described his insect fieldwork. A senior scientist who had studied mountain birch larval outbreaks for decades paused processing her samples to generously talk about her own embodied experience from the field, sharing nuances and uncertainties that underpin scientific knowledge but remain absent from the concise science posters on the station walls.

These unplanned encounters created an informal collectivity that shaped my sense of the local ecology beyond what I could ever formulate through my own experience and tools. They reminded me of philosopher of science Isabelle Stengers’ notion of an “ecology of partial connections,” which foregrounds the importance of relearning the collective habits of knowledge-making against their erosion by the dominant extractivist and productivist ethos of contemporary academic culture. In her words, the goal of reflective slowing down is not to reproduce individualistic practices, but to find time to learn from others by engaging with them in ways that do not erase difference, allowing oneself to be transformed by what is learned, and recognizing the debt owed to those transformative encounters.6

Rewilding the botanical gaze needs slowing down, but also something more: practising exposure to different ways of thinking, staying with the partiality of positions and holding space for the frictions and hesitations that emerge when we want to be collectively in the world. In this, nonhuman others can act as guides, prompting shifts in attention and ways of knowing that we might not arrive at alone.

Some time after my stay in Kilpisjärvi, I was driving along a highway in north-eastern Poland. In the ditch between the road and a monotonous field, I caught sight of a cluster of massive, dry angelica stems. They resembled figures standing by the road as if watching the road and passing cars. In a split second, I recognised the species. I thought about the angelicas far up north and felt a renewed sense of botany as a connection.

References

- Subramaniam, Banu. Botany of Empire: Plant Worlds and the Scientific Legacies of Colonialism. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2024. Feminist Technosciences series.

- Halberstam, Jack. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

- Gandy, Matthew. “Attentive Observation: Walking, Listening, Staying Put.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 114, no. 7 (2024): 1386–1404.

- Rautio, Anna-Maria, Weronika Axelsson Linkowski, and Lars Östlund. "“They followed the power of the plant”: historical Sami harvest and traditional ecological knowledge (Tek) of Angelica archangelica in northern Fennoscandia." Journal of Ethnobiology 36, no. 3 (2016): 617-636.

- Heikkinen, Hannu I. 2021. “Holding Ground and Loitering around: Long-Term Research Partnerships and Understanding Culture Change Dilemmas of Indigenous Saami.” Time and Mind 14 (3): 459–74.

- Stengers, Isabelle, and Stephen Muecke. Another science is possible. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2018.