In 2025, Santtu Laine was selected for a month-long art & science research residency in Tokyo by Bioart Society, BioClub Toyko and the Finnish Cultural Institute in Japan. The following text reflects his research and thoughts during the residency period in Japan in November-December 2025.

My artistic practice and conceptual focus explore the intersection of materiality and memory through seaweed-based bioplastics. This work is grounded in sustainable art practices that consider ecological impact and the life of materials. During the BioClub Tokyo residency, my research focused on experimenting with marine bacteria to bio-etch and shape bioplastics in a controlled laboratory environment. Part of my reaserch was also to learn about the traditions and centuries-old methods of seaweed processing and kanten (寒天) production in Japan.

Arriving to Tokyo

A residency in Japan was a dream come true in many ways. I began my research and initial experiments with seaweed-derived bioplastics about five years ago. Now, I was here, where it all began more than four centuries ago.

The first time I visited Japan was in 2015, when I traveled to Tokyo and Osaka for a university group show. Since then, Japan has been on my mind, and I have been waiting for the chance to return. Now after a decade I was finally back. As soon as I arrived in Shinjuku from Narita Airport, it all came back to me in a flash: busy, noisy, hectic streets, flashing lights, the smells of the city, and people rushing to who knows where. Everything felt the same as last time.

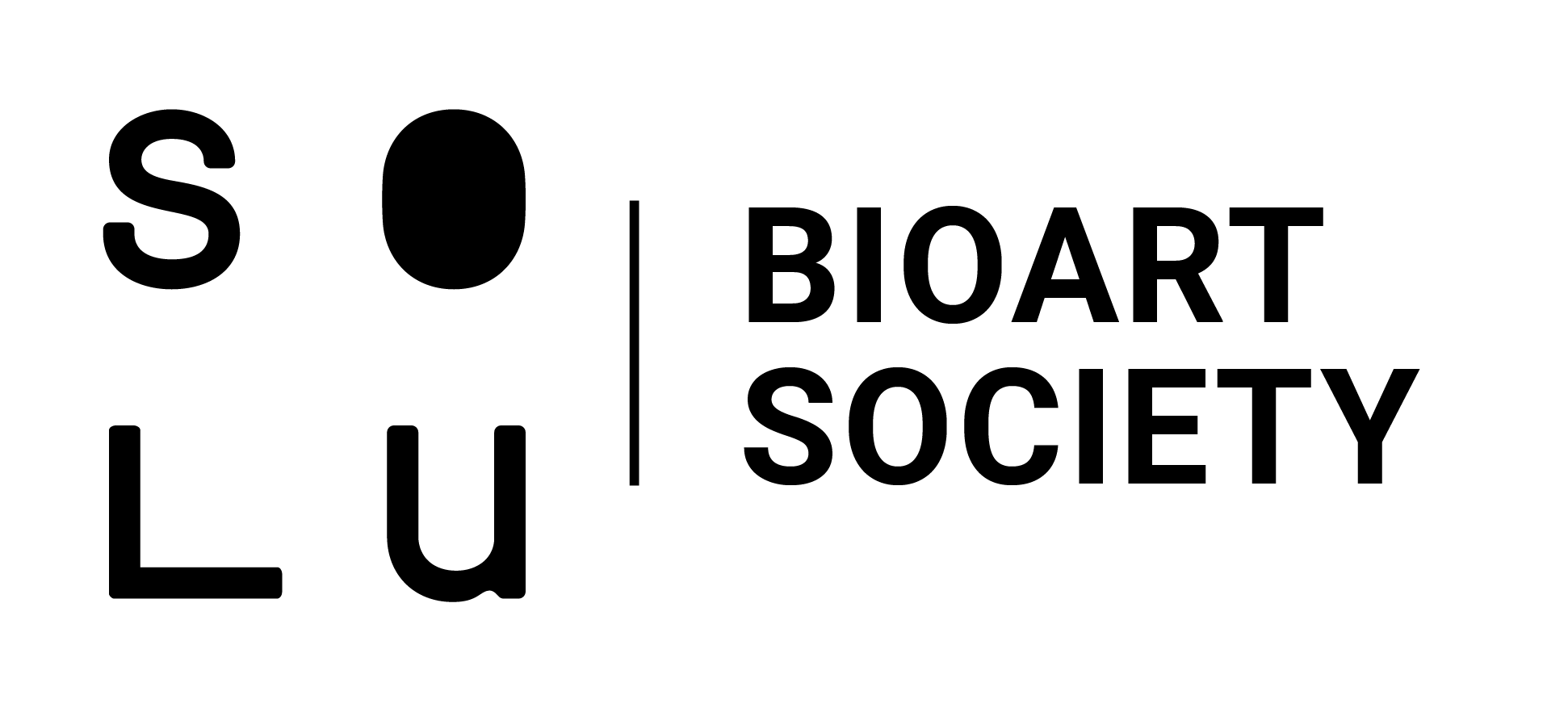

Image: Artist Talk at the BioClub Tokyo

Image: Artist Talk at the BioClub Tokyo

After a few days of settling into Tokyo’s rhythm, it was time to roll up my sleeves and get to work. The residency got off to a pleasant start with an artist talk at BioClub Tokyo. Meeting the other members and engaging with the audience’s many questions made me feel instantly welcome.

Waking up the bacteria

For my experiments I decided to use a common marine bacteria found in all the oceans around the globe. The bacteria, Pseudoalteromonas atlantica, is a species similar to other bacteria in Pseudoalteromonas genus. I wanted to use this common bacteria to be able to replicate the possible effects back in Finland. These marine bacterias are agarolytic, meaning they produce agarases – enzymes that break down agar, a polysaccharide found in red algae. My plan was to experiment if I could use this degradation process to bio-etch seaweed based bioplastics.

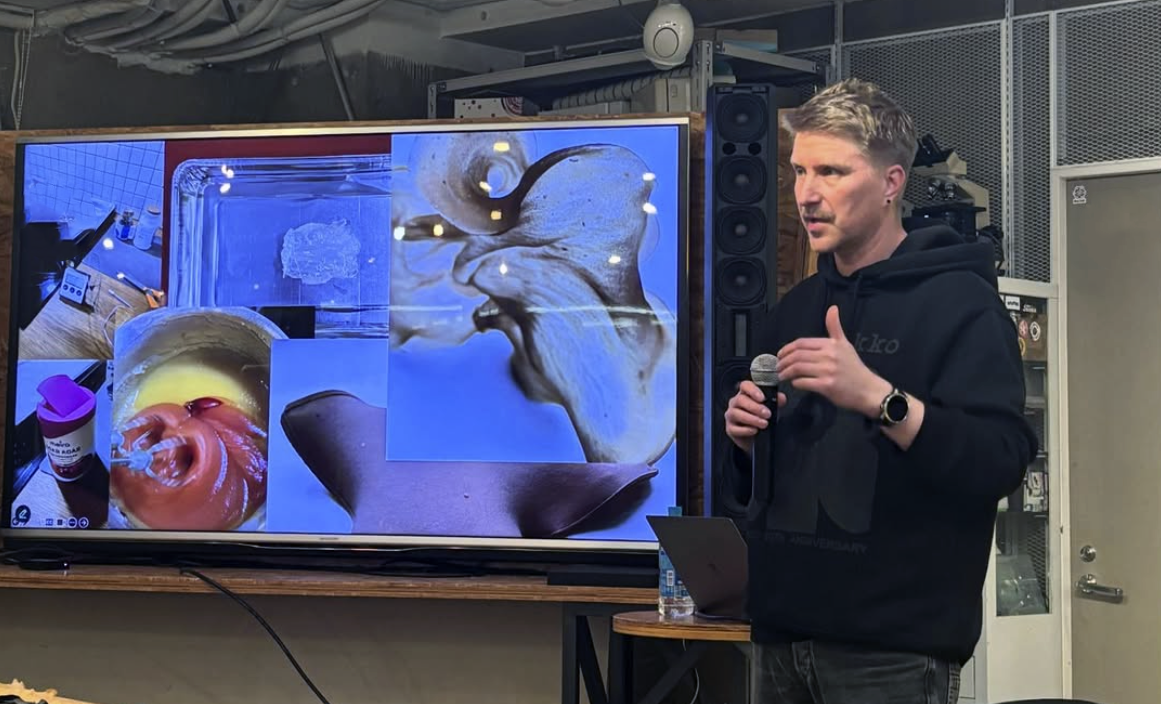

My initial plan was to isolate bacteria from the shores of Tokyo, but to speed up the process, we decided to order them directly from Japan’s National Biological Resource Center. When I arrived at the lab, the bacteria were already waiting in the freezer. This was my first time working in a controlled lab environment with living bacteria so I was really excited. After I was introduced to the lab and its safety procedures, it was time to break the seal, wake up the bacteria, and feed them some fresh marine broth.

Image: Shohei Asami helping to revive freeze-dried bacteria for culture media.

Image: Shohei Asami helping to revive freeze-dried bacteria for culture media.

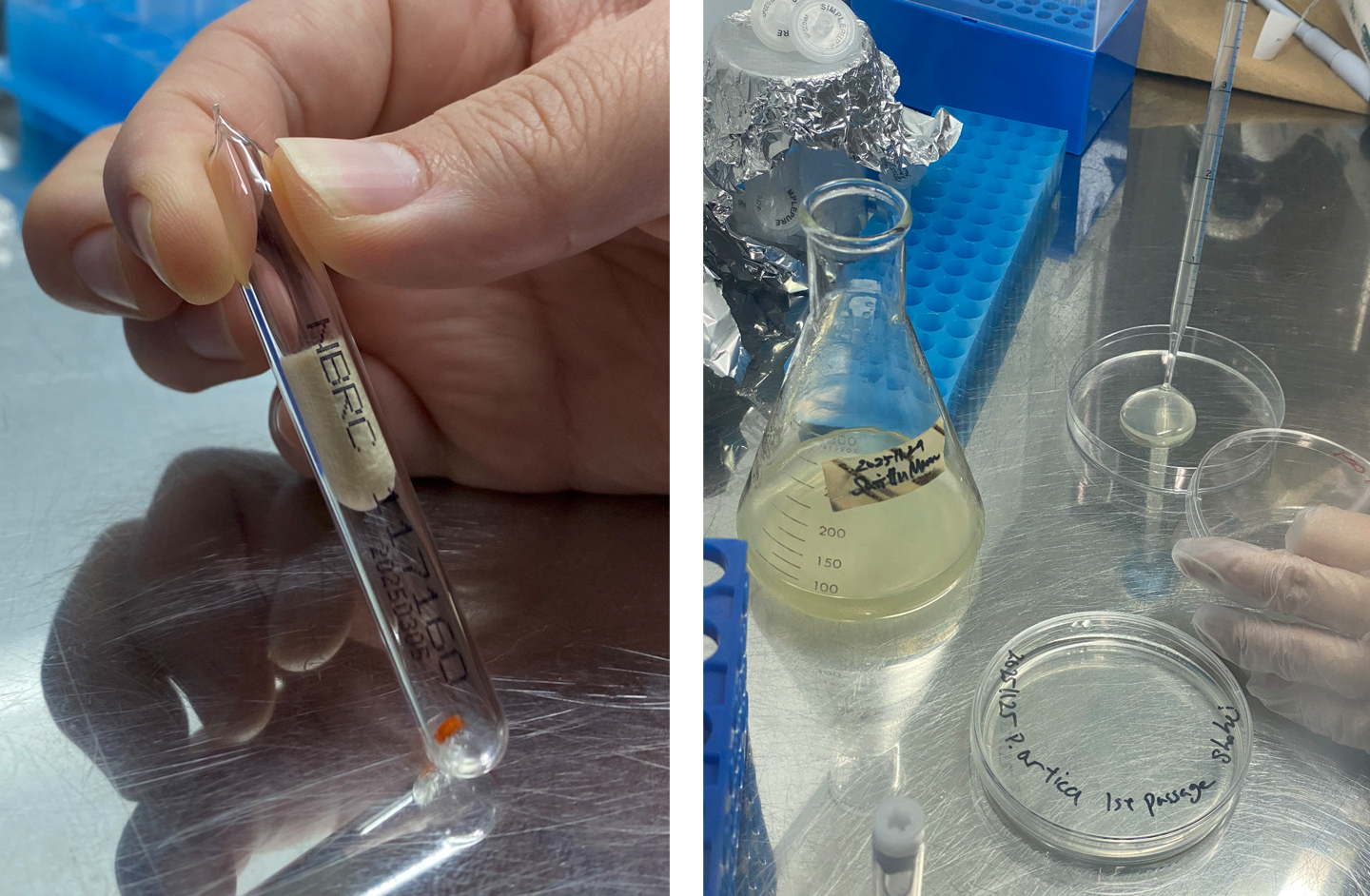

The bacteria had a cultivation temperature of 20 °C, so it was possible to grow them at room temperature. After a few days, the bacteria were already growing well. I could get my first look at them under a microscope and begin testing the degradation process using agar sheets.

Image:Petri dishes with bacteria and a first look at Pseudoalteromonas atlantica under the microscope.

Image:Petri dishes with bacteria and a first look at Pseudoalteromonas atlantica under the microscope.

After two weeks, the bacteria were showing strong growth in the Petri dishes, and I was able to expand my degradation tests to several agar plates. It turned out that the degradation process was taking longer than I had initially expected. This left time for other experiments as well.

Getting to know the traditions of kanten production

Japan has a rich history and deep-rooted traditions in seaweed utilization and production. Agar, or agar-agar—referred to as kanten (寒天) in Japan—is a gelatinous substance processed from red seaweeds and has played an essential role in Japanese cuisine and confectionery. Kanten is often used in making wagashi (和菓子), a traditional Japanese confectionery and tokoroten (心太, ところてん), a Japanese jelly noodle dish.

The tradition of its use in Japan dates back to the early Edo period, when it was discovered in Kyoto by accident around the 1650s. In addition to the use of agar in the food industry this gelling agent has in modern days become important in the preparation of culture media and other bacteriological applications. Agar is widely used in modern microbiological laboratories around the world. Despite significant technological advances, no alternative has fully matched agar’s versatility, reliability, and ease of use for solid culture media.

Agar is also an excellent raw material for producing sustainable bioplastics. By combining agar-based biopolymers with other ingredients like natural fibers and waxes it is possible to create bio-composites that can be utilized for numerous purposes. Material properties of the agar based bioplastic can be modified depending of the needs of the final application. Agar-based bioplastics are already used in food packing and other applications where biogradable - or even edible - packing is needed.

I was very keen to learn about the traditional methods of processing Japanese tengusa-seaweed (Gelidium amansii) and the production of kanten. I felt that understanding and studying these traditional practices could not only enhance my own processes with seaweeds, but also inspire new ideas and improved techniques, all while honoring the craftsmanship of the past.

Factory visit to Mizuno Kanten

Two areas in Japan are famous for their natural kanten: Ina-shi in Nagano Prefecture, which produces bo (stick) kanten, and Yamaoka-cho in Gifu prefecture, which is known for ito (string) kanten. In Yamaoka-cho, kanten is produced every winter from November to February. Kanten production began there in the early Taisho era (1912-1926). The quality of agar depends heavily on natural conditions. It can only be produced under specific weather patterns, typically requiring periods of dry, sunny weather as well as exposure to cold temperatures. The traditional method of kanten production is slowly disappearing due to rising temperatures caused by climate change. Today, only 15 producers remain in Japan.

I managed to organize a visit to Mizuno Kanten, a family-run company in Yamaoka-cho in Gifu prefecture. The visit was something I had been anticipating since I started planning my residency. The company is known for its high quality kanten that is favored by long-established wagashi makers like Toraya. In rural Japan, English is not widely spoken, so there was a language barrier I had to overcome. Fortunately, with the support of the Finnish Institute in Japan, I was able to hire a translator who assisted me during my visit.

Imgae: Meeting at the Mizuno Kanten with Motoaki Mizuno and translator Ai Naruse

Imgae: Meeting at the Mizuno Kanten with Motoaki Mizuno and translator Ai Naruse

Image: Tengusa seaweed (left). Dried ito (string) kanten after processing (right)

Image: Tengusa seaweed (left). Dried ito (string) kanten after processing (right)

At the factory, I was warmly greeted by Motoaki Mizuno, both a company representative and one of the family members and founders. He guided me around the factory, explaining each step of their manufacturing process. I discovered that Mizuno Kanten produces agar each year from September trough April. A rhythm their family has maintained for three generations.

Image: Tengusa seaweed soaking and washing

Image: Tengusa seaweed soaking and washing

The process begins by thoroughly washing the tengusa seaweed for two days. The washed seaweed is then boiled for 12 hours in large containers. To achieve the ideal consistency and taste for wagashi, Mizuno blends over ten different types of wild tengusa. While going through the process, we also discussed local seaweeds and how tengusa (Gelidium amansii) is facing a significant decline due to environmental changes, particularly rising ocean temperatures. This has led to increased reliance on imported seaweeds, as well as a shift toward alternative ingredients and modern production methods.

Image: Filtering process with natural pressure using concrete weights

Image: Filtering process with natural pressure using concrete weights

After boiling, the wet tengusa is strained by placing it, together with its liquor, into a filtering bag and weighing it down with a concrete weight. This process relies on natural pressure, as using a machine could release unwanted extracts. After extraction the agar-liquid is pumped into a small containers and left to solidify at room temperature for approximately 20 hours.

Image: Wooden tentsuki tool and soldified tokoroten rods (left). Tokoroten strands layd on a reed mat (right)

Image: Wooden tentsuki tool and soldified tokoroten rods (left). Tokoroten strands layd on a reed mat (right)

The liquid is allowed to set into tokoroten, which is then extruded into slender strands using a large tentsuki tool. The strands are then spreaded on to a reed mats for outside drying. I also had the opportunity to try this traditional tool. I have to admit, using it looked much easier than it actually was.

Image: Learning how to use tentsuki tool

Image: Learning how to use tentsuki tool

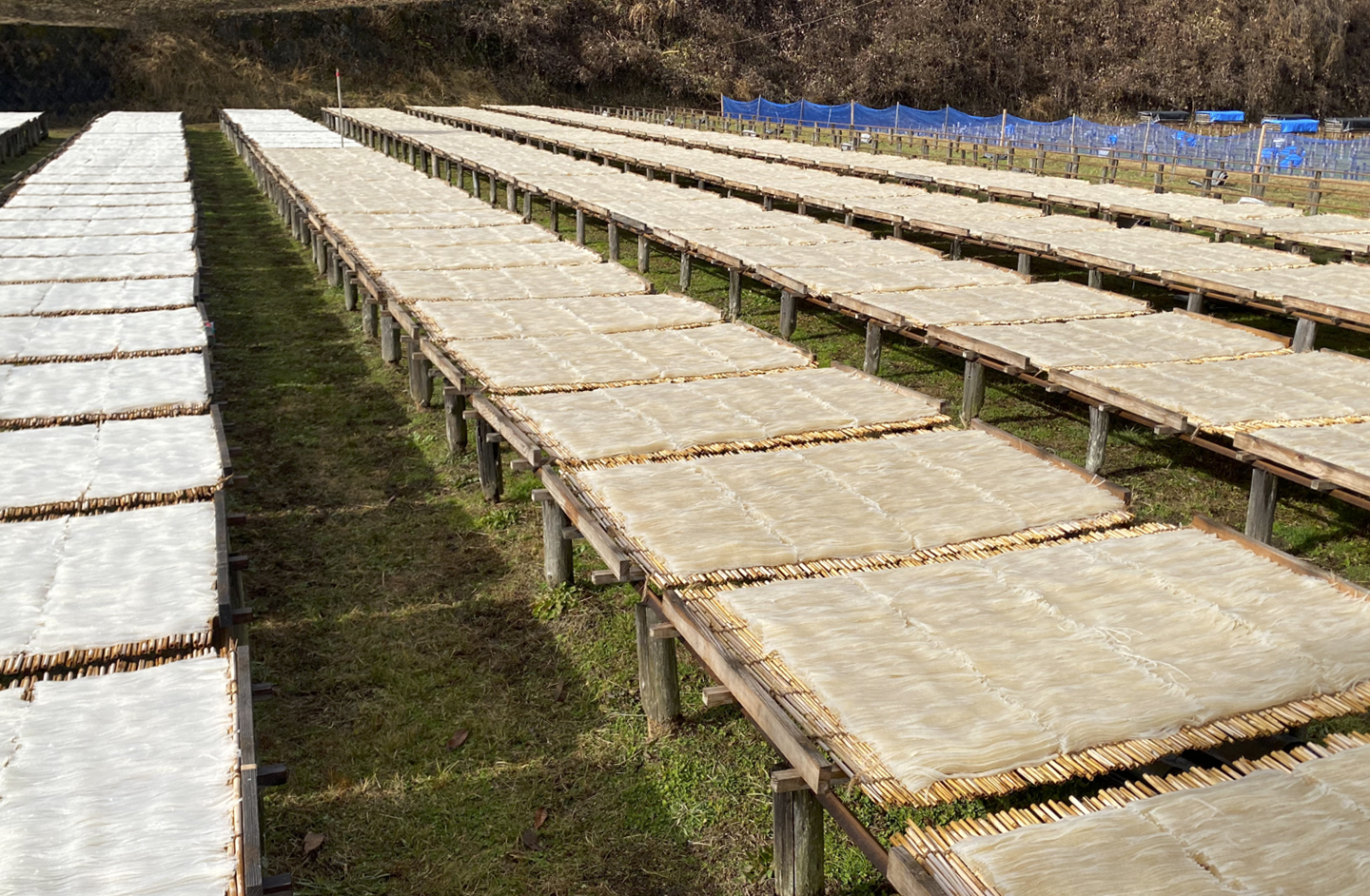

Reed mats with tokoroten strands are then laid out in the fields to dry over a period of about twenty days. The strands are repeatedly frozen and dried until they are completely dry. Freeze-drying is an important process in making tokoroten to fine agar. The process takes advantage of the climate of Yamaoka-chō. When I tasted the dried kanten made by Mizuno, it barely had any taste at all. This was very different from the powdered agar commonly available in Europe. European agar usually has such a strong taste that it is almost impossible to hide it when cooking. I’m not at all surprised that Michelin-starred restaurants in Europe choose Japanese kanten over agar powder for their delicacies.

Image: Quality control of dried kanten sheets at the factory

Image: Quality control of dried kanten sheets at the factory

Image: Freeze-drying tokoroten into kanten in the fields

Image: Freeze-drying tokoroten into kanten in the fields

The visit was both inspiring and insightful. On a technical level, I learned new ways to process seaweeds and how to enhance their properties to create bioplastics tailored to my artistic practice. Equally meaningful was witnessing how the community sustains centuries-old traditions—practices deeply intertwined with the cycles of nature, built on mutual respect and awareness. It was a vivid reminder of how material, culture, and ecology are inseparably connected.

The future smells blue?

One of the most intriguing side paths was learning about indigo dyeing and getting to know the indigo vat in the lab, which the previous artist-in-residence, Lau Kalker, had started over a year ago. The vat was still in good shape and was gently nurtured by the BioClub members.

Image: Getting hands blue with Gina Goosby (left). Indigo vat (right)

Image: Getting hands blue with Gina Goosby (left). Indigo vat (right)

One experiment I wanted to try with Indigo was dyeing pieces of bioplastic. I couldn’t find any information about it, so to the best of my knowledge, it had not been done before. This made me eager to see how it would work: how the bacteria would react and how the coloring would appear in the bioplastic.

Image: Indigo dyed agar-bioplastics (left). Dye samples: kakishibu and indigo (right)

Image: Indigo dyed agar-bioplastics (left). Dye samples: kakishibu and indigo (right)

To my surprise, the end result was stunning! Since the agar-based bioplastic has a yellowish hue, the dyeing process transformed it into a leaf-green color. I also experimented dyeing with kakishibu – a Japanese natural dye made from fermented persimmons. The results with these natural dyes were so inspiring that I plan to continue exploring this path back in Finland.

Bio-etching with bacteria

When the residency perioid was coming to an end, it was time to evaluate the results and findings. My experiments in bio-etching seaweed-derived bioplastics with bacteria were based on a well-documented process of Pseudoalteromonas atlantica’s behavior in nature. This type of bacteria plays an important role in the breakdown of organic marine biomass in the oceans. What I was hoping to observe were visible patterns or ‘carvings’ forming on the surface of the agar sheets.

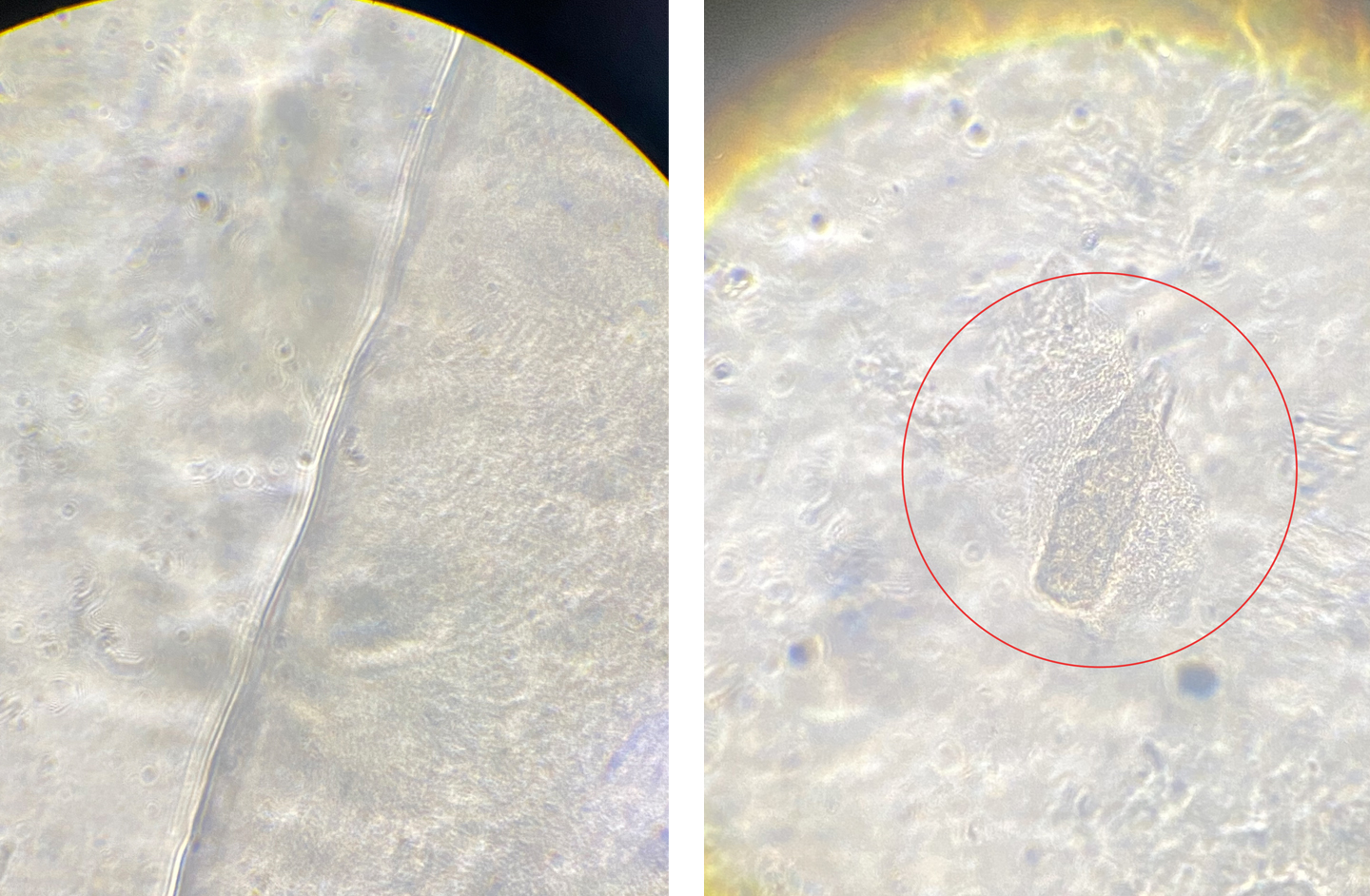

Image: Agar degradation ripples on the right side (left). Localized enzymatic degradation of agar (right)

Image: Agar degradation ripples on the right side (left). Localized enzymatic degradation of agar (right)

The experiment had a combination of successes and failures. The degradation process was clearly visible both under the microscope and with the naked eye. The enzymes produced by the bacteria functioned as expected: they degraded the agar sheets, causing them to become thinner. The anticipated pattern formation did not occur as expected. While I could observe some degradation marks under the microscope, I had hoped for visible results on a millimeter scale. Instead, the changes occurred on a microscopic scale.

At the BioClub Tokyo Lab

One month in Japan flew by in a flash. Just as I felt I was getting started, it was already time to wrap everything up and pack for the journey home. Even though my lab experiments didn’t turn out exactly as I had hoped, I learned so much along the way. I could say that everything else was a success. I came to Japan with a small set of ideas, and I’m returning with a head full of new experiments and directions to explore!

Farewell to Bioclub Tokyo

I want to express my heartfelt thanks to all the organizations that supported my research and this residency: the Finnish Institute in Japan, the Bioart Society, and BioClub Tokyo. A special thank you also to Sohei Asami, Gina Goosby and George Tremmel for their help, guidance and inspiration. Thank you also all the amazing people I met during this trip and all the BioClub members.

Santtu Laine is a Finnish multidisciplinary artist based in Helsinki, Finland. Working across installation, sculpture and moving image, Laine’s practice focuses on exploring alternative and sustainable methods of art-making, with a particular emphasis on bioplastics derived from seaweed. Laine holds a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Time and Space Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki, and a Bachelor of Arts in Photography from BTK University of Art & Design in Berlin. His work reflects a deep commitment to ecological awareness, integrating innovative materials and processes to address humanity’s relationship with the environment.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/santtu.laine