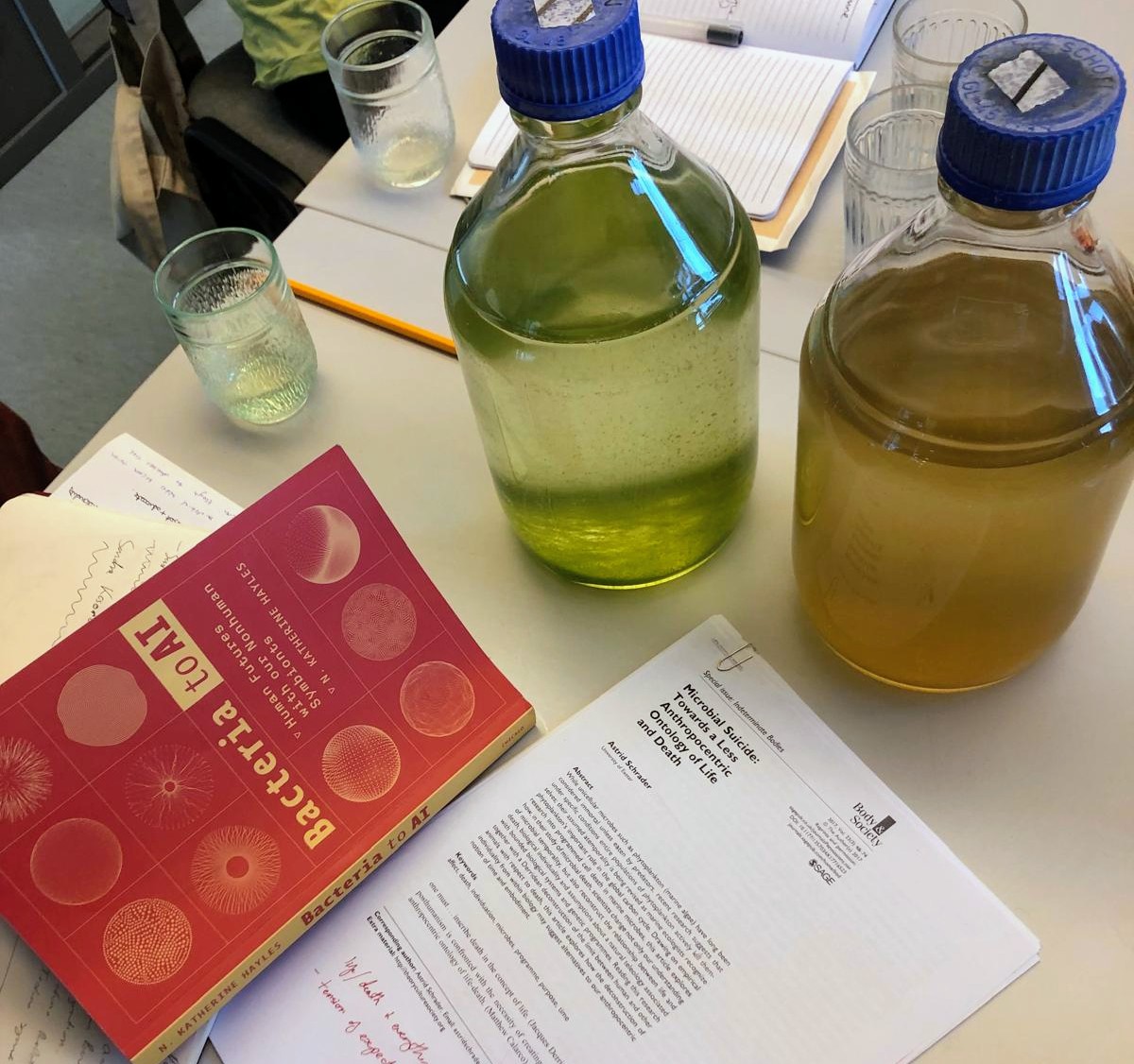

From Spring to summer 2025, Bioart Society ran three consecutive ‘Reading Matters’ sessions on N. Katherine Hayles book Bacteria to AI: Human Futures With Our Nonhuman Symbionts. Artist and writer Kirsty Hendry and curator and writer Helen Kaplinsky, were invited to co-facilitate these reading circles, selecting chapters of focus that linked with their own research.

Here, Hendry & Kaplinsky reflect on some of the questions that emerged from the group discussings and how they are still thinking with these in various ways within their own practices.

In addition to reading Hayles’s Bacteria to AI, we turned to other sources in the third session to help us grapple with the wider implications arising. These included: Lucy HG Solomon and Cesar Baio’s essay, An Argument for an Ecosystemic AI: Articulating Connections across Prehuman and Posthuman Intelligences; K Allado-McDowell’s talk On Neural Media and their The Known Lost exhibition description; and Sianne Ngai’s text Theory of the Gimmick.

These become key references in Hendry & Kaplinsky’s responsive texts and form part of an extended reading list developed by the reading group participants that can be found at the bottom of this page.

Kirsty Hendry is an artist and facilitator (usually) based in Glasgow, Scotland who develops projects exploring bodily knowledges and science fictions. Kirsty and their commensal collaborators work across writing, artist moving image, and other practices of metabolising information. Kirsty’s work is often collaborative, creating and developing methods of co-production to facilitate collective enquiry within community engagement and participatory contexts. This can include the general public through workshops and public programming; with a wide range of community groups; and with interdisciplinary groups of artists and/or professionals from music, science, performing arts, health & social care. Kirsty was undertaking a 6 month Artist Residency at The Centre for the Social Study of Microbes in Helsinki at the time of the reading matters sessions.

Helen Kaplinsky (she/her) is a curator and writer based between Finland and the UK. Over the past decade her projects have spanned questions of postdigital identity, femininity and ownership. She has curated several projects involving cyberfeminism(s) and its echoes in current feminist art practice - the focus of her current PhD studies at the Exhibition Research Lab, Liverpool John Moores. In recent years she has worked on events and exhibitions with HAM (Helsinki Art Museum), Tallinn Kunstihoone, Helsinki Biennial, Barbican, Tate (Modern and Britain), Whitechapel Gallery and Transmediale Festival. She co-directed London project space Res between 2015-2020 and has curated collection-based exhibitions with the Contemporary Art Society and the Arts Council Collection. Her writing has been published by Routledge, Artmonthly, Institute of Network Cultures, Liverpool University Press and Bristol University Press among others.

Kirsty Hendry

I got my hands on Bacteria to AI a month into my residency at the Centre for the Social Study of Microbes at the University of Helsinki. With bacteria on the brain, I was curious about the implied relationship between Bacteria and AI in the aforementioned title. Was Hayles positioning bacteria and AI on the same evolutionary lineage? Naturalising a ‘new’ technology through an ancient antecedent? Or was it more a gesture to signal the sheer vastness of the ground covered; two polarities, two supposed extremes (the ‘natural’ and the ‘artificial’, the ancient and the futuristic) that could be linked through the surprising commonality of ‘cognition’?

In one of our reading group sessions I remember saying “this book is saying one thing but believes something else entirely”. Now—Glasgow, Winter—I’m returning to this book and the notes and thoughts made in relation to it then—Helsinki, Spring. I return in the hope that the passage of time and distance will afford me a different perspective and provide new insights. But I only become reacquainted with that same feeling. It may seem ungenerous or churlish to focus on tone but it is what I am left with—what sticks— every time I read, think, or discuss this book. This short reflection (and the discussions and parallel readings that make such reflection possible) are an attempt to explore this non-cathartic feeling, a frustration that I’m attempting to articulate, that feels perennially on the tip of my tongue.

I had started trying to put this feeling into words by excerpting direct quotes from the book that I felt could exactly encapsulate some of the logical fallacies and cognitive dissonances that I found so irksome. But this approach failed to capture what reading this book made me feel so I abandoned it. Looking for answers elsewhere, I turn again to Sianne Ngai’s writing on tone, as we did in the reading group. In Ugly Feelings she defines tone as “a text’s affective bearing, orientation, or ‘set toward’ its audience and world”. I realise that my issue is not so much with what Hayles is saying, but that how she is saying it seems to undermine her stated intentions. My frustration is subtextual, aimed at something implicit, residual, something that lingers—like a bad smell without an obvious (or quotable!) source.

In the opening sentence of Bacteria to AI, Hayles states the central purpose of the book is “to combat anthropocentrism and suggest other perspectives more conducive to survival and flourishing”. While Hayles does stress that we humans cannot avoid anthropomorphism completely, for we see with human eyes and think with human brains, for Hayles, the key manoeuvre to combat anthropocentrism lies in wresting cognition from the grip of human supremacy, for “[t]he linchpin of anthropocentrism is cognition”. Our obnoxious and misguided belief that ‘we’ (humans that is) are uniquely and supremely cognisant is the root cause of our hubris, our greed which have now come to their logical conclusion: climate catastrophe. Hayles’ defines cognition (chosen deliberately because unlike consciousness or intelligence, cognition does not carry the same lofty baggage) as the ability to interpret information and make choices or selections based on those interpretations and therefore ensures a ‘principled way’ to distinguish between cognitive acts and material processes. While I believe this sentiment is offered up as an attempt to arrive at a more egalitarian application of cognition, for me, Hayles’ siloing of cognition from material processes and practices seems to undermine their own argument. Can cognition be so cleanly cleaved from material processes? Is cognition not always already a material process?

I think of Elizabth A Wilson’s analytical exploration of the ‘mindedness of matter’ in Gut Feminism. Wilson cautions against the partitioning of the body into ‘minded and unminded substance’ writing that “this gesture does violence to the rest of the body and to other natural and social systems”, not simply because it castigates the ‘unminded’ to the peripheries but because it also curtails and narrows possibilities for understanding the ‘minded’. Binary thinking, in establishing meaning via opposition also impoverishes the capacities and possibilities for meaning. To me, Bacteria to AI whiffs of unresolved tensions between advocating for a move to thinking beyond binaries, while not quite being able to let the impulse go.

While I am in absolute agreement that ecocide is a violence of ‘our’ own doing, it is in these sections of Bacteria to AI where the tone begins to bristle. An affective tell that the motivations underpinning this project are more driven by shame and guilt rather than responsibility and accountability; an impulse towards overcorrection that verges on misanthropy. Misanthropic in the sense that the tenor of Hayles’ argument suggests that all of humanity share equal culpability for the climate crisis, which to me further inculcates fatalistic thinking and obfuscates a (relatively) small percentage of humanity with grotesquely outsized power and greed. Isn’t positioning humanity as uniquely terrible yet another form of anthropocentrism? Whether we see our species as the pinnacle of creation or the ruinous blight destroying the planet—both are still a product of the same old binary thinking. Simply inverting the hierarchy does not automatically subvert the hierarchy.

Bacteria to AI’s central call to action is a need to rethink basic assumptions about human and non human intelligences, but one such basic assumption that goes under interrogated in Hayles’ argumentation is the assumption that the category of ‘human’ is applied and upheld equitably, justly, and consistently. Think of all our fellow human beings who are violently denied their most basic, fundamental human rights, as I write this and as you read this. The category of ‘human’ is not a unified one—neither is its antithesis ‘non-human’, a wastebin taxon which runs the gamut from binbags to the blue whale. These categories rely on such broad distinctions that they become almost meaningless and, in the process, ensure that the constituent members of both categories are treated with a lack of care, nuance, and specificity. I’m not sure if Hayles’ theory of cognition offers means for breaking down binaries more than it serves to reinscribe them along different lines?

Helen Kaplinsky

My own research considers how feminist storytelling is mediated by and represents digital technologies in symbolic realms. I was drawn to reading Bacteria to AI firstly through my investment in the questions Hayles asks about the mutual transformation of literary criticism and digital technologies and, relatedly, the social imaginary of wet-ware technologies, which involve bacteria and other life forms as living computers. In this brief response I will focus on the first topic in relation to AI and literary criticism, which is primarily covered in Chapter 6 ‘Inside the Mind of an AI: Materiality and the Crisis of Representation’. For those interested it’s also, but to a lesser extent, within Chapter 7. ‘GPT-4: the Leap from Correlation to Causality and Its Implications’ and Chapter 9 ‘Collective Intelligences: Assessing the Roles of Humans and AIs’.

Before I speak more about the specifics of Hayles intellectual engagement, I would like to provide a TL;DR (Too Long; Didn’t Read) summary of the book's project and some background on my expectations based on readings of her previous work. The book's premise unravels in its reading, based solely on the apparent chasm between the solid ground of the terms she defines and the way she stylistically seeks to make arguments across the quite different chapters. For example, in Chapter 3, Hayles fleshes out ‘Technosymbiosis’ as a contemporary condition in so-called ‘developed’ countries, thus “Whereas the cyborg typically implies some kind of physical fusion, symbiosis can designate our present state of living in close proximity with computational media through interdependent relations” (98). This concept, with which I am in some agreement, suggests a material and cognitive entanglement that, in its embodiment, is so complex that it is a specious project to analyze one element alone. Following this logic, the possibility for computation is contingent upon and entangled with all life forces. I conclude that it is not possible to simply provide an account, as Hayles does, of the ‘developed’ countries without taking into account the sometimes inverse and mostly extractive relations towards all matter that sits outside the designation of ‘developed’. It’s fair to suggest, in this and many other cases, that such omissions could have been addressed through an intensive editorial process that I can only imagine more senior academics, such as Hayles, are, perhaps, less willing to engage with. This is pure speculation; however, it is a practical question I came to ask myself while reading. This inclination is heightened by my contrasting feelings towards her earlier writing, which is more sharply edited.

My prior experience of reading Hayles, in relation to literary criticism and digital technology, still inspires my current work. I’m thinking of her analysis of an iconic piece of cyberfeminist electronic literature - Shelley Jackson's, ‘Patchwork Girl’ (1995) - which can be found in Chapter 6 of her 2005 book My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts. Hayles weaves a textured argument for embodied e-lit criticism. She describes how e-lit—a format defined by a combination of image, text and hyperlinks—produces a feminine reader. The monolith of male defined authorship and linear narrative is unraveled through disorderly clicking and reading flickering, partial fragments on the screen. Hayles embraces the messiness that emerges from human ethics and human-machine collaboration, which results in a divine subjection to the material, Frankenstinian monstrosity of it all. I realise now that this intertextuality, both form and function woven into the criticism, is perhaps a critical high point for Hayles and reflects an insight she was able to bring to bear in a male-dominated field of electronic media arts for an earlier generation. For those with an interest in the history of cybernetics and looking for an understanding of what posthumanism meant thirty years ago, Hayles How We Became Posthuman (1999) is a classic and was compulsory reading amongst my generation of post-internet millennials during my training (now fifteen years ago!) I continued to follow Hayles work, and found Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious (2017) a compelling piece of thinking at the intersection of cognitive science and the humanities. The proposition of a “planetary cognitive ecology” in which nonconscious unicellular organisms play as much of a role as human conscious beings, provided one of the more convincing narratives to resonate with artistic projects looking to fungi and deep-time bacteria as wet, material knowledges beyond human exceptionalism.

Returning to the focus upon AI and literary criticism in Bacteria to AI, I was excited to read Hayle’s take on GPT literature. This approach to writing in collaboration automatically generated text was termed by its proponents Emily Segal and K Allado McDowell “deepfake autofiction”, after they began their iterative, esoteric experiments with large language generators around 2021, when the GPT-3 model was first made available to an elite set of creatives. I expected palpable excitement from Hayles (who I previously considered a feminist theorist) concerning the latest chapter in electronic literature’s divine and queer subjection to Frankensteinian human-machine relations. Sadly, I came away from the reading disappointed as it turns out Hayles is no fan of GPT lit. In addition, I was struck by her lack in self-reflectivity, where the contents of her analysis repeatedly contradicted wider arguments, particularly for Technosymbiosis. As an example, Chapter 6, she sets up a false dichotomy that pits human and AI content against each other. She asks, “Does it matter if a text is written by a human or AI?” Her answer - “yes” - is followed by a characterisation of AI as necessarily lesser on all accounts. According to Hayles, AI’s material reality and crisis is that it simultaneously lacks material embodied emotional experiences, whilst also suffering from information overload. The latter causes the AI to overfit its outputs to hallucinated patterns. She ends the chapter by promising that all is not lost, in the future, AI will extend its horizon by incorporating sensory data (which she, anyway, acknowledges is already happening with DALL- E image generator p.163).

Hayles swings inelegantly between outdated post-structuralist takes on AI—it is the harbinger that ends human exceptionalism and the standard ‘death of (human) author’. These arguments, whilst not entirely irrelevant, have not been updated or rethought in light of the current context of GPT lit. I read her ‘hot take’ on the death of the modern romantic male author in relation to her e-lit analysis in the early 2000’s. Then, in 2017, she challenged human exceptionalism by writing about nonconscious life. It’s absolutely legitimate for her to build on her previous work; however, for readers new to her work she doesn't make these arguments with her earlier, more convincing prose, and she also doesn’t pour the same passion she had for e-lit into the current generation of artists producing AI literature. Luckily, there are other scholars taking generous and exciting approaches, answering my question: how does subjectivity become monstrous yet again? One name that is worth dropping is poet and creative coder Allisson Parrish. Parrish is spot on when she describes “the sacred and vulgar, colloquial and arresting” in K Allado-McDowell’s “deepfake autofiction novelette” Amor Cringe, an early example of GPT lit, made with early access to the AI model in 2022.

Flags were raised regarding the unnecessarily personal attack Hayles repeatedly makes on the author K Allado-McDowell, who, whether you like their work or not has been a prominent figure in AI literature and has supported many other artists in their experiments in the field (in 2015 they established the Google Artists + Machine Intelligence program). Hayles dismissively states that K makes false claims about co-authorship (149). K describes their approach to authorship as ‘Post-human co-creation’ where “human and nonhuman voice…produce a braided, multidimensional, reading experience” (kalladomcdowell.com/read). While Hayles bitingly states K, is in fact a “human author” (260) — a notion that seems wholly counter to the sentiment of human-computational entanglement that is central to Hayles own theory of Technosymbiosis. Upon studying the footnote that accompanies this, I found alarmingly wry comments concerning K’s pronoun ‘they’. Hayles’s approach to gender and pronouns was also raised when we read the introduction, specifically regarding Karen Barad’s misgendering.

Perhaps it is no surprise that Hayles has issues with moving beyond gender binaries, as ultimately, the reading group broadly agreed that her stories about bacteria, large language models and CRISPR technologies in Bacteria to AI re-inscribe received scientific boundaries, thereby continuing dominant Western global-north genealogies of postwar cybernetics. So, while Hayles fell short of my expectations, I would like to conclude on a note that offers another route for thinking about AI and bacteria, based on what else I have been reading.

Novelist and philosopher Sylvia Wynter combines threads across literary criticism and the natural sciences—a combination not unlike Hayles. However, Wynter’s additional lenses of Black Studies and decolonialism highlight the limited White perspective of posthumanist scholars, including Hayles. Reading an interview between Wynter and scholar and Katherine McKittrick, it struck me that Hayles is uncritically trapped within what they refer to as “Man’s episteme, its truth, and therefore its biocentric descriptive statement” (Chapter 2 of ‘Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis’ 2014, 23). Wynter’s most well-known phrase ‘After Man’ theorizes an alternative to this given essentialist idea of knowledge via the power of storytelling. She draws on Fanons notion of ‘sociogeny’ (broadly how social, rather than biological forces shape psychic life) and ‘mythoi’, borrowed from Cesaire (shared narrative as a fundamental and poetic aspect of liberation).

In the context of colonial ecocide, rather than doing away with the human altogether, Wynter reappropriates scientific categorisation towards symbolic truth: “In my own terms, the human is homo narrans” (25). The entanglement of biological matter and digital technology is shown to be a set of forces that are shaped by the boundaries of language and narrative at the societal level. So let’s take care and pay attention not to take implicit stories about natural and computational science for granted. How artistic practices evolve and collaborate with techno-scientific forces, according to Wynter, is a co-evolution with the dynamics of myth, which is always hiding in plain sight.

Bacteria to AI: extended reading list

In our reading group, as generally happens, our discussions often led us away from the book and towards other thinkers being referenced in the writing and around the table. From this we have compiled an extended reading list for further reading on topics of Bacteria to AI dealing from a range of writers with differing perspectives.

K Allado-McDowell | On Neural Media | Long Now Talks, Apr 11, 2025 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eu3ygZh8pY8&t=235s

Key words: artificial neural networks, AI slop, broadcast media, immersive media, biometrics, postdigital identity

—The Known Lost, exhibition at Swiss Institute, New York, 2025 (description/documentation): https://www.swissinstitute.net/exhibition/k-allado-mcdowell-the-known-lost/

Key words: biospheric ancestry, spiritualism, extinction, interspecies relations, neuro-opera, monument, spiral path

—Pharmako-AI, Ignota books, 2021

Key words: GPT literature, AI creative collaboration, experimental lit, hallucinatory, cyberpunk revival

Karen Barad, ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3): 801–31, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1086/345321.

Birch, K., 2017. The problem of bio-concepts: biopolitics, bio-economy and the political economy of nothing. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 12, 915–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-017-9842-0

Keywords: critique of conflating bio-conepts to circumvent more complicated STS analysis

David Graeber, The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. 2015. https://libcom.org/article/utopia-rules-technology-stupidity-and-secret-joys-bureaucracy-david-graeber

N. Katherine Hayles, Bacteria to AI: Human Futures With Our Nonhuman Symbionts, The University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Key words: unconscious cognition; nonhuman and artificial intelligences; human superiority of human intelligence; integrated cognitive framework (ICF); meaning-making practices of lifeforms.

—Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Key words: neuroscience, cognitive science, “planetary cognitive ecology” - involving plants and unicellular organisms, algorithms (techno) and animals

—My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Key words: code, language, subjectivity, cyberfeminist art, “intermediation” - where digital media and pre digital practices meet (eg. electronic text and paper books).

—How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Key words: history of cybernetics, Macey conferences, post-war consensus

Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan, Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Microbial Evolution, 1986

Keywords: evolutionary biology, microbial ancestry, interdependence, symbiogenesis

Katherine McKittrick (ed.) Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Duke University Press, 2015.

Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick, 2017

Key words: labour relations, labour abstraction, devices, technology, capitalist aesthetic phenomenon.

Allison Parrish, “The umbra of an imago: Writing under control of machine learning”, 2020 https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/art-and-ideas/the-umbra-of-an-imago-writing-under-control-of-machine-learning/ . This text was originally printed in NO NO NSE NSE —Jenna Sutela co-published by Kunsthall Trondheim, Serpentine & König Books.

Lucy HG Solomon and Cesar Baio, An Argument for an Ecosystemic AI: Articulating Connections across Prehuman and Posthuman Intelligences, 2020

Iida Turpeinen, Beasts of the Sea (Elolliset), S&S, 2023

Elizabth A Wilson, Gut Feminism, Duke University Press, 2015